Predictions of doom are as bad as denialism. There is much we can do to shift the trajectory of climate change.

We currently face the greatest challenge of civilised humanity. We are heating the planet, upending the balance of the ecosystem that birthed us, risking livelihoods, crop failure and drowning cities.

In November, in Glasgow, politicians from 189 countries will gather under the gaze of the world’s media and the glare of activists, to shuffle through the decks of compromises and solutions at the Conference of the Parties (CoP) 26th gathering. The outcome, we hope, is significant mitigation and reversal of global warming.

As with Covid-19, there are solutions. They are both technical and dependent on behaviour change.

The Political Landscape

The scale of the political economy impacted by the need to change has dwarfed the results of earlier conferences. Blame for the condition of our atmosphere is clear. The industrial revolution, starting 200 years ago, was enabled by sources of energy that produce CO2 as a polluting by-product; it enriched Europe and North America – who are now very concerned about the future. Meanwhile, the newer industrial countries (India and China) have as their primary focus a more immediate concern: increasing the quality of life of their populations. Put another way, the early polluters (who continue polluting) have already enriched themselves at the expense of the planet; the newer ones “need” to do so and would justifiably like the early polluters to pay for the cleanup.

Added to this, less industrialised countries (Nigeria, Venezuela) have fossil fuels as the basis for their economies and want to continue extracting them.

So, the politicians arrive in Glasgow with conflicting agendas as the risks increase for “life as we know it”.

The Mechanics of Global Warming

How does it work? Sunlight passes through the atmosphere and warms the surface of the planet. Much of this heat goes back into space as infrared radiation, but some are absorbed by (mainly) CO2 molecules in the air and retained. The more CO2 in the air, the more heat is retained, and the warmer the earth and its oceans. More heat means more energy in the system giving rise to more extreme events. Flows and currents in the air and sea which are driven by convection and the spinning of the earth are shifted; the distribution of heat around the earth changes and becomes more intense. Icecaps melt.

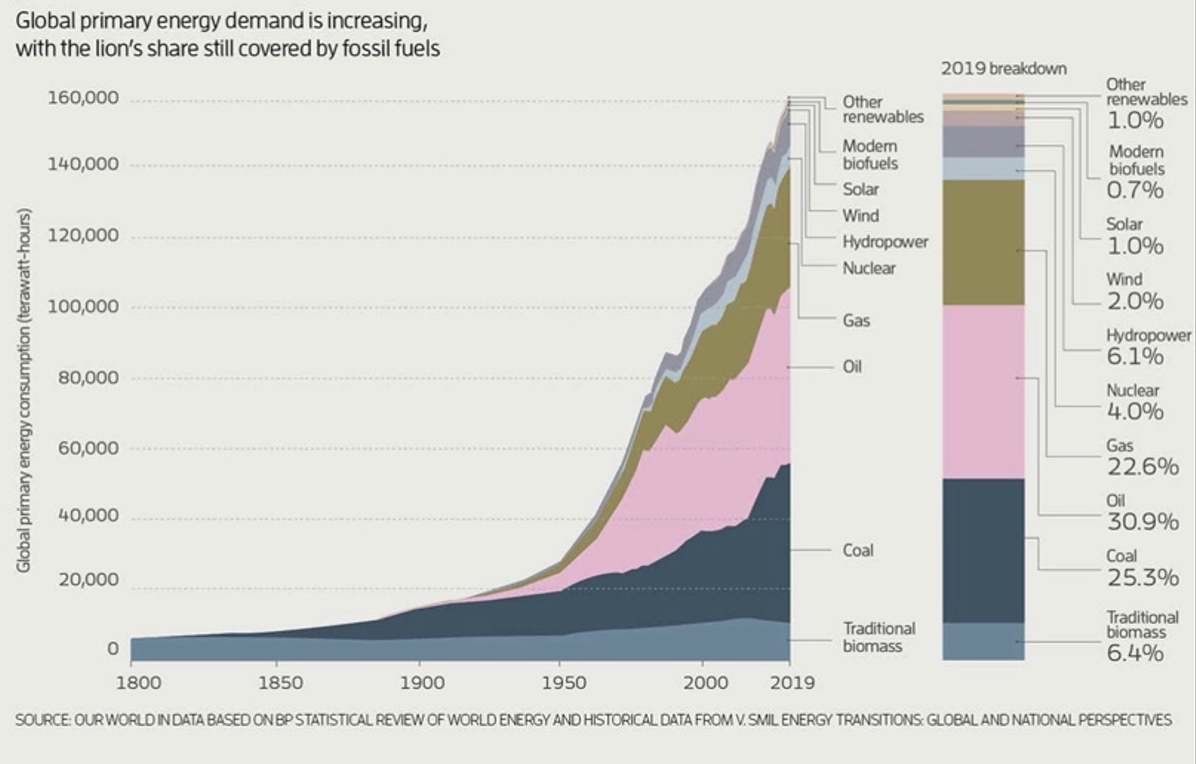

These are extremely complex systems. Precise predictions of future weather (what is happening day by day) are difficult, but the global trend in climate (what is likely to be normal in the longer term) is undeniable. The link to the burning of coal, oil and gas by industrialising economies and concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere (resulting in increasing temperature) is not disputed. Today we generate about 80% of our energy by burning the big, bad three – all of which were originally sequestered in the earth by natural processes over millennia.

The oceans, soil and forests still extract CO2 from the atmosphere but can no longer match our production; and the concentration in the air has grown from pre-industrial levels of about 280 to around 430ppm as we spew out 100+ million tons (mt) every day. This up from 40mt in 1970.

So, climate change is happening, and we are responsible.

Much work is being done to improve the accuracy and complexity of our predictive models. Dimensions now factored in include:

- The role of methane (a more potent warming gas) being released from melting permafrost in Russia and elsewhere;

- The ability of oceans to absorb CO2 as they heat up and acidify;

- The change of ocean currents as icecaps melt. The Gulf Stream keeps Europe’s climate milder;

- The reduction in the earth’s ability to sequester CO2 due to clearing forests for palm oil and pasture in the Congo and Amazon.

All of these add to the probability that we are sliding towards disaster. As we understand more of these feedback loops, the urgency to act should accelerate. Without change, we will exceed a 3-degree increase in temperature and melt the ice caps. One result would be the drowning of all coastal cities – do we need more reason to invest in change?

What Are We Doing?

It was as far back as 1964 that a climate study was commissioned by US President Lyndon Johnson in response to concerns raised in the scientific community about the risks and role of CO2 pollution. It reported then with the basics of what we know to be true today. Despite this knowledge, we have since then increased the levels of CO2 pollution by 250%. Denial and lobbying by industry groups continue in the face of unassailable science.

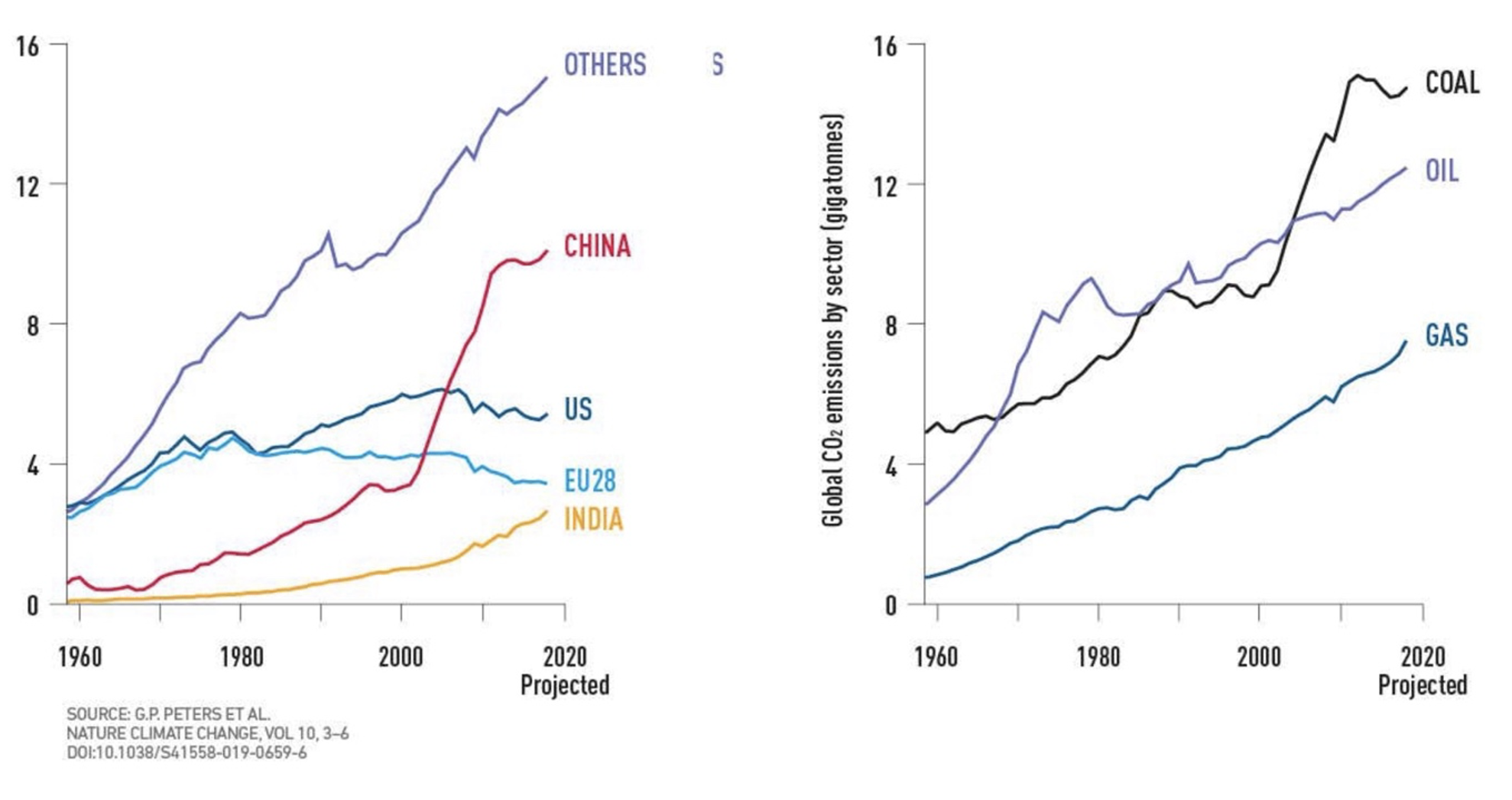

But while some countries have stepped up, as globally we continue to do too little, and to take too long to do it. It took 30 years from the time LBJ’s team warned of what was coming before 154 countries signed a UN Convention on Climate Change to build a technical response. During that time, we had moved from emitting 15 gigatons of CO2 a year (1970) to 36 when the Paris accord was signed, to over 40 today. Since 2000, China and India have trebled their emissions whilst most developed countries have stabilised or dropped slightly.

CoP Paris, signed in 2015, is now binding on 189 states and covers countries emitting 97% of anthropogenic CO2. Its target is to stop global temperatures rising by more than 2 deg C above pre-industrial levels and, if possible, to limit the rise to 1,5 deg C.

Why 1,5?

There is really no right number – the lower the level of pollution, the better, as we are already systemically out of sync. By 1990 we were close to +1 deg C, and capping it at +2 deg C seemed achievable. As, even on the most ambitious targets, we will be producing CO2 for many years, the concept of net-zero has been coined. This means that the volumes of CO2 we continue to produce should not exceed the combined ability of natural systems and our efforts to sequester. Achieving this balance is net-zero.

This target is complicated by politics and nationalism, exploiting loopholes and uncertainties in the agreements. Some corporates and industries try to delay being forced to change or shut down. In this context, trading carbon credits has emerged as an interesting intervention. Emitters buy or fund savings in another geography or industry to offset their own pollution.

Eskom has a huge opportunity here if only we can shift the stonewalling action of some politicians and their cronies.

So to Impact

Global warming is not about more comfortable days on the beach in currently colder climates. Heat kills all by itself. People already die in steadily increasing numbers as more, longer and hotter heat waves strike. It kills directly by heat exhaustion and less directly by crop failure. Record heatwaves and fires have already become frequent enough not to make the front pages of the news.

In polar regions, if all the ice were to melt (and it won’t for a century or more even if global emissions are unchecked) sea levels will rise by more than 50m and no coastal city will survive. If only the West Antarctic ice sheet melts which needs less than +2 degrees to become likely, it alone holds enough water to raise sea levels by 3,5m. That’s enough to take out much of London, Cape Town, the Nigerian delta cities and New York.

Of course, we don’t need all the ice to melt for trouble to begin.

The fact of the matter is that with the swirling masses of air and sea, all areas will not be equally impacted. Some might even cool as ocean currents shift. Some will be wetter and some experience more drought, ending the agricultural practices in those geographies. Climate refugees are already a reality but this will be one of many increased stresses the world’s economy will have to deal with. Climate change has been characterised as a poverty multiplier that no economy will escape.

The rise in temperature and its consequences can be limited or even stopped with current technology and understanding. There is no one silver bullet and a combination of multiple actions is the only hope. Slavish commitment to a single approach without considering implications and opportunities within the solution would be a mistake.

Land Use Management

Tree planting is one of these complex interventions. There is no doubt that trees, especially mixed, wild forests or tropical jungles are carbon sinks. So an idea is to plant a trillion trees. Swapping pasture for cattle feed to the forest will make a big difference. Were 1,2 trillion trees to be planted on 900 million hectares of land, it would store 150 billion tons of carbon annually – but would mess with the traditional braai big time, as beef and mutton supplies dwindle. (900 million hectares of forest are stripped of trees around the world, with the Congo and Amazon being cut down at increasing rates for palm oil, timber and pasture.) At the same time, planting monocultures is an environmental disaster as the environment for large numbers of species will disappear.

Land use in general is a tool seldom considered. South Africa cultivates 500k hectares of wheat and 2,7m of maize. Our farming practices in the main should be shifted towards the regenerative – practices that improve soil’s ability to hold carbon and usually improves crop yield. Conservatively, these farms could shift to storing an estimated 100kg per hectare per annum, taking 320 000 tons of carbon from the air every year. If a significant part of the 5bn hectares planted globally can be directed to regenerative agricultural practices, it would make a huge contribution.

Transport & Industry

A full 90% of all transport is powered by oil, using a quarter of our total energy production. Not all of this can be replaced by non-carbon sources but much can be improved. Clean electricity and green hydrogen for land transport will go a long way.

The production of cement, metal and paper means drives large production of CO2. Solutions are at hand but generally at smaller, tentative scales with a higher cost of production. Greater take-up of these cleaner approaches is being legislated in some countries. Supply chain management of CO2 output by subcontractors to global businesses will also help. Recycling metal and glass helps, although recycling in the plastic industry seems irredeemable with less than 5% of all plastics being recycled.

Power Generation

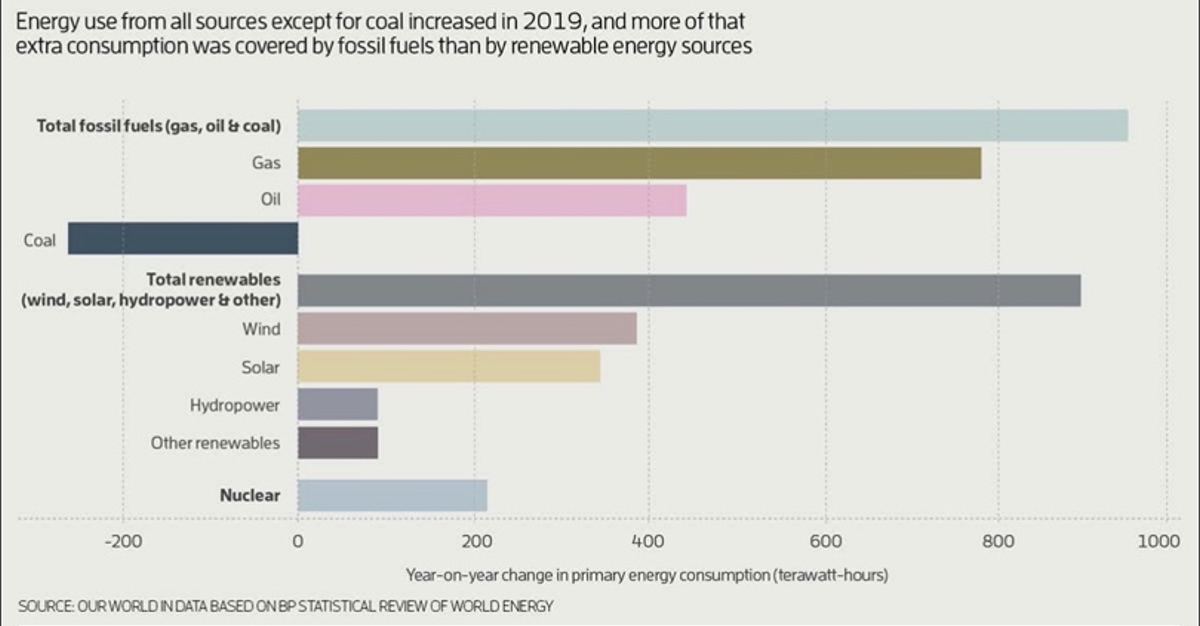

The most achievable in the available timeframe remains renewable electricity. The transition has begun in some earnest though only a quarter of the world’s electricity – 10% of our total energy consumption – is produced by modern, less C-intensive resources. Achieving net-zero requires all electricity to be generated without producing CO2. This is partly because aviation, some industry and much of shipping will continue to use fossil fuels.

We also dream of a scientific breakthrough that will save us. The two technologies most spoken about are carbon capture and nuclear fusion.

The first has been shown to work at a small scale in about 25 instances, but never at the scale of our big coal-fired power stations, and much work is required to bring the tech up to scale and to bring down the currently prohibitive costs. The generally accepted view is that this is a decade away but worse, that the cost will remain too high to be used.

With regard to nuclear fusion (which involves fusing two hydrogen atoms to form one of helium with a significant release of energy in an extremely high-temperature plasma and no nasty by-products unlike nuclear fission which is in use today and involves splitting uranium atoms), a number of practical attempts have been made to contain the plasma required for the reaction as it is so hot that no solid material can survive contact. The Tokamak – a machine that confines the plasma using magnetic fields in a doughnut shape that scientists call a torus – is the leading contender for this task. However, most scientists expect that this stage of the fusion process will take 15 years to achieve; and that the next will take a decade more – so, 30 years before the holy grail of clean, very large scale electricity from fusion reactors commercially in use. A number of the world’s billionaires have begun investing alongside and in competition with governments in this space.

ESKOM

South Africa isn’t one of the legacy polluters, like Western Europe and North America. Nor is it one of the “new wave” of polluters, like China and India. But it’s certainly punching above its weight in terms of volumes of CO2 pumped into the air: there is some debate about whether we are the 12th or 13th biggest greenhouse gas producer in the world.

Eskom is single-handedly responsible for nearly 40% of the 477 million metric tonnes of CO2 South Africa contributes to the crisis annually. Our per capita contribution, at 8,2 tonnes per year, is bigger than both that of China (7,05 tonnes) and of India (1,96 tonnes).

So we’re not victims of this global crisis: we are contributors, and we need to act now, and fast, to become part of the solution.

The power utility has taken measures to find green funding. Naturally, this is conditional on “green” behaviour. In funding our two newish, large coal-fired power stations ESKOM contracted to install pollution limiting technology. This has been omitted in the build with vague promises to retrofit in the future. At the same time with global financial markets somewhat oversupplied with money and CoP26 on the near horizon, we have the opportunity to trade any carbon savings we make through retiring two or three of our old, decrepit (and most polluting) coal-fired power plants ahead of schedule. This is in exchange for an estimated R80bn which could be set against ESKOM’s government-guaranteed debt. Standing in the way of this, it has been suggested, is successful lobbying by suppliers and transporters of coal, influencing decisions of government.

Of course, arguments that jobs will be lost have weight. These jobs are going to be lost anyway and the preparation for a “just transition” is in the hands of our government. These losses should also be measured against the dire effects these power stations have had on the health of those living and working in the areas and on the environment in the northeast of our country and Mozambique.

Reducing dependency on coal and amplifying the contribution of renewables are both readily achievable. South African power generation requires systemic change that is both deep and broad: a just energy transition plan can be completed – one that moves away from carbon-intensive energy generation towards clean technologies in such a way that jobs are retained and communities supported. With this in place, South Africa will be able to access the opportunity of carbon trade and concessional climate financing.

De Ruyter is convinced this is critical to a just transition; he also suggests that key partners seem willing and that South Africa is well placed to access this funding. Elements in government seem, however, to be stonewalling. For more than two critical, expensive years, there has been too little movement on the related proposals presented by the expert presidential task team. We now have until COP26 in November this year to present our plan.

In conclusion, we’re part of the bad guys. There are technical solutions available to us locally and globally. Little will be achieved without informed leadership with the courage to resist lobbying and be open to the complex, hard work that needs to be done. South Africa’s biggest win is within ESKOM but this seems to be outside the power of management to achieve with political stonewalling limiting options.

A just transition means a better life for all.