Prof Eberhard chairs the presidential task team mandated to resolve Eskom’s financial and technical woes. He is a power man through and through; he directs the Power Futures Lab at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business; was the founding Director of the Energy and Development Research Centre; and has put in a lifetime’s work in the energy sector across the developing world. In the short term, Prof Eberhard’s task team is to focus on fixing Eskom; in the longer term, the intention is to reposition the landscape of electrical power in South Africa.

In his powerful talk, Prof Eberhard unpacked some of the devastating trajectories of the last decade. Regarding Eskom’s finances, he pointed to the following:

- Employee numbers went up by about a third between 2007 and 2018 – but employee costs went up more than 300%, from R9,4bn to R29,4bn.

- Although electricity sales declined over the period, from just over 218 000 GWh to just over 212 000 GWh, revenue skyrocketed from around R39,4bn in 2007 to R175bn last year. How does that work? Well, the price per kWh went from 18c to R85.06.

- Still this wasn’t enough to keep the utility afloat, so debt securities and borrowings soared from around R40,5bn to around R388,7bn.

“Eskom is now in the classic death spiral,” Prof Eberhard said, “the more they charge, the less we use, and the more they need to borrow to stay afloat.” And it’s not getting better; unable to generate enough capital to cover its running costs and service its debt , Eskom’s hand is perpetually out for government bailouts.

There is a technical dimension to the collapse, too. In an environment of rent-seeking and corruption, Prof Eberhard said good people left, and the utility now has an extreme competency shortage; over 20 years, the general deterioration of skills levels has accelerated the damage of the wasted nine years.

Prof Eberhard is, however, optimistic; he believes that this crisis presents an opportunity for South Africa. The business model on which Eskom is built no longer fits any market, anywhere. “Globally, we are seeing unprecedented innovation in energy technologies, services and business models. South Africa should embrace this transition. It makes sense economically and is best for our environment.” President Ramaphosa’s SONA announcement about Eskom’s unbundling is the crucial first step on this journey.

The unbundling is intended to enable focussed management on each of the dimensions of the business: generation, transmission and distribution. In turn, this will translate to cost transparency, fair contracting, savings and efficiencies. As least-cost power crystallises focus, private investment and competition will accelerate in a virtuous cycle of improvement.

“There has been a very clear instruction,” Prof Eberhard said about his task team’s brief, “to resolve the problem in a way that also links to sustainable structuring.” Although privatisation of the utility is not on the cards, contributions from independent power producers (IPPs) are a critical part of this equation. The costs in the renewables sector have fallen dramatically: 50% for wind and 80% for solar PV. Renewable energy IPPs have now reached grid parity in South Africa. “The next renewable energy auction or competitive procurement will result in bids of lower than 50c/kWh, which is half of Eskom’s average selling price and less than a third of Medupi or Kusile.” The reliability challenge of renewables can be addressed in a vision that complements renewables with flexible resources such as gas, hydro, pumped storage and utility scale batteries.

Prof Eberhard has some thoughts, too, about addressing the financial death spiral through a climate financing deal. Through the Paris Agreement, South Africa has a modest and achievable carbon commitment, which presents real opportunities to access highly concessionary climate money.

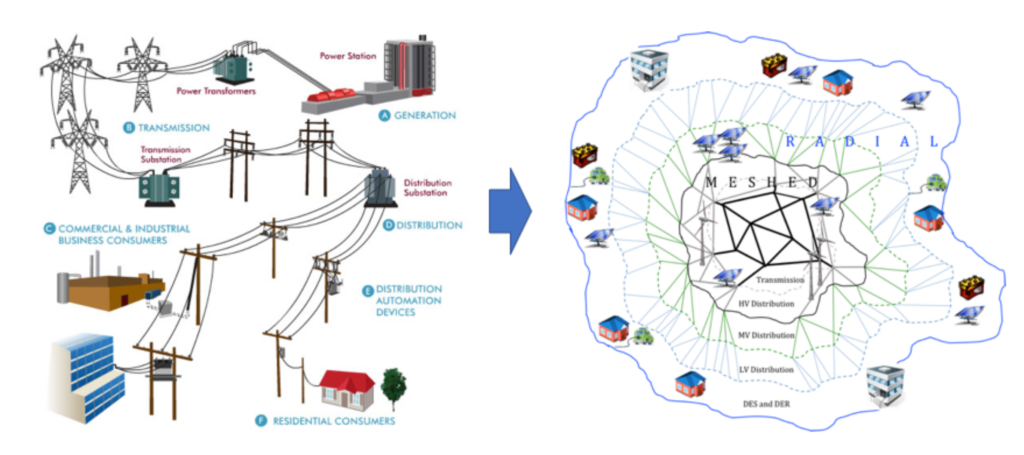

Over the course of his talk, Prof Eberhard presented a charismatic energy picture in which traditional centralised and linear grids are transformed into a network, with consumers sharing in the production of the power they use, and the excess being pulled into the pool:

In the animated conversation that followed, the point was made that in this time of great change, there will be winners and losers, and the challenge will be to manage the transition in a just way. Workers and communities who currently depend on the traditional coal-based generation approach will be assumed to be the losers, naturally – but this need not be the case, said Prof Eberhard, and planning a winning transition will take this into account.

Understandably, given the deeply intertwined roots of vested interest that have brought us to this, there is cynicism about whether this – the third time a restructuring has been attempted – will succeed in fixing the situation.

Prof Eberhard’s appeal to ALI Fellows was heartfelt. “There are counter-narratives linked to special interests. We – the task team – are not skilled in telling the story that needs to be told. We need help in developing and spreading evidence-based narratives that support this transition.”

The story he believes needs to be told, at grassroots level and everywhere else, is that South Africa is at a watershed, poised to realise a vision for how an apparently irredeemable mess can be turned around. We are, he believes, starting a journey over the course of which we will demonstrate what a properly integrated, sustainable power generation network can be. It’s an exciting, promising time.